The Case for AlphaZero: Openings and Pawn Progression

January 20, 2022 | By Timothy Han SM ‘22

image description: silver chess pieces on a chess board.

This piece was written at the Veritas Forum 2020, an annual writing program offered by the Augustine Collective. Students from various universities work with writing coaches to write articles about virtue in the sciences or social sciences.

On December 6, 2017, AlphaZero, a new chess program developed by Google, changed the world. [1] AlphaZero made its world premier in a match against Stockfish, the most dominant algorithm in chess history. Ever since IBM’s DeepBlue defeated world champion Garry Kasparov in 1997, engines have reigned supreme over humans in the world of chess. Stockfish, the latest in a long line of formidable chess algorithms, could evaluate 70 million moves per second; AlphaZero could only manage 80,000. An open-source program that has been ceaselessly improved since its debut in 2004, Stockfish came armed with countless formulas, strategies, and even endgame sequences to plan for every contingency.

AlphaZero’s developers, on the other hand, taught it only the basic rules of chess, and nothing else. After waking the program up for the first time, the DeepMind team let AlphaZero practice against itself. A total novice at first, AlphaZero experimented as a baby does. It played random moves, followed no strategy, and tried out every arbitrary combination of which it could conceive. Just like a toddler learning to walk, AlphaZero crawled slowly, haltingly, to checkmate. Then, on slightly sturdier limbs, AlphaZero completed another game. And then another. After nine hours of practice, AlphaZero played Stockfish.

Correction: AlphaZero pummeled Stockfish. In 100 games, AlphaZero won 28, drew 72, and never lost. In a bulletin for Chess.com, journalist Mike Klein wrote: “Chess changed forever today. And maybe the rest of the world did, too.” The birth of AlphaZero opened up new realms of possibility for artificial intelligence. Engines like Stockfish are designed to think like computers, following a strict set of pre-programmed guidelines to optimize for guaranteed value. AlphaZero, instead, learned like a human, thought like a human, and played like a human.

Ever since Darwin and Nietzsche reduced man to the league of ordinary creatures in the late 19th century, the boundaries of human identity have been ever more narrowly constrained. For much of Western intellectual history, what set human beings apart from our mammalian counterparts was the concept of a Platonic soul. However, in the wake of the Enlightenment, we have come to reject many of the underlying assumptions that justified theories of human exceptionalism. The rejection of theism coincided with a rejection of the soul. Sartre and de Beauvoir’s existentialism told us that we had no inherent teleologies. Devoid of non-material indicators of identity, we have become, in the words of the 19th century biologist Thomas Henry Huxley, “conscious automata.”

In this context, AlphaZero, which was specifically designed to imitate the human mind, encourages us to rethink the ontologies of both artificial intelligence and human beings. In our modern, materialist framework, is AlphaZero really that different from us?

Developing Key Pieces

In 1948, the computer scientist Alan Turing, whose team at Bletchley Park broke the Nazi Enigma Code, began to develop the first chess algorithm. Named Turochamp after himself and his colleague David Champerowne, Turing played the first games of computer chess using pen and paper, following the explicit rules of the algorithm, after failing to implement the algorithm on a computer.

Building on the shoulders of giants, early chess programs became robust, hulking engines, dominating opponents by the brute force of their computational speed. The IBM DeepBlue system that eventually defeated Kasparov could evaluate 200 million moves per second. But, being only machines, these early models relied on written algorithms to tell them how to evaluate positions. Programs like Stockfish possess incredibly advanced sets of algorithms, detailing when bishops are more valuable than knights or what priority should be given to the king’s safety. However, no matter how complex the system of evaluation, the programs are still susceptible to slight and subtle errors. For example, a big problem with many early algorithms is that they calculated positions largely based on ‘material,’ or how many important pieces one player had compared to the other, instead of the ‘position’ where those pieces were.

AlphaZero brought an entirely novel approach to the game. Instead of calculating many positions, AlphaZero chose only those moves which, according to prior experience, it thought would prove most promising. For every move it considered, AlphaZero played out 800 complete games stemming from that move. It then compared how often various moves led to victory and chose the highest-scoring move. This system of prioritization and playing out a bulk number of games is called a Monte Carlo tree search. Given Monte Carlo’s gambling etymology, AlphaZero played all of its hypothetical games entirely at random, betting on the law of large numbers to show it the most favorable moves.

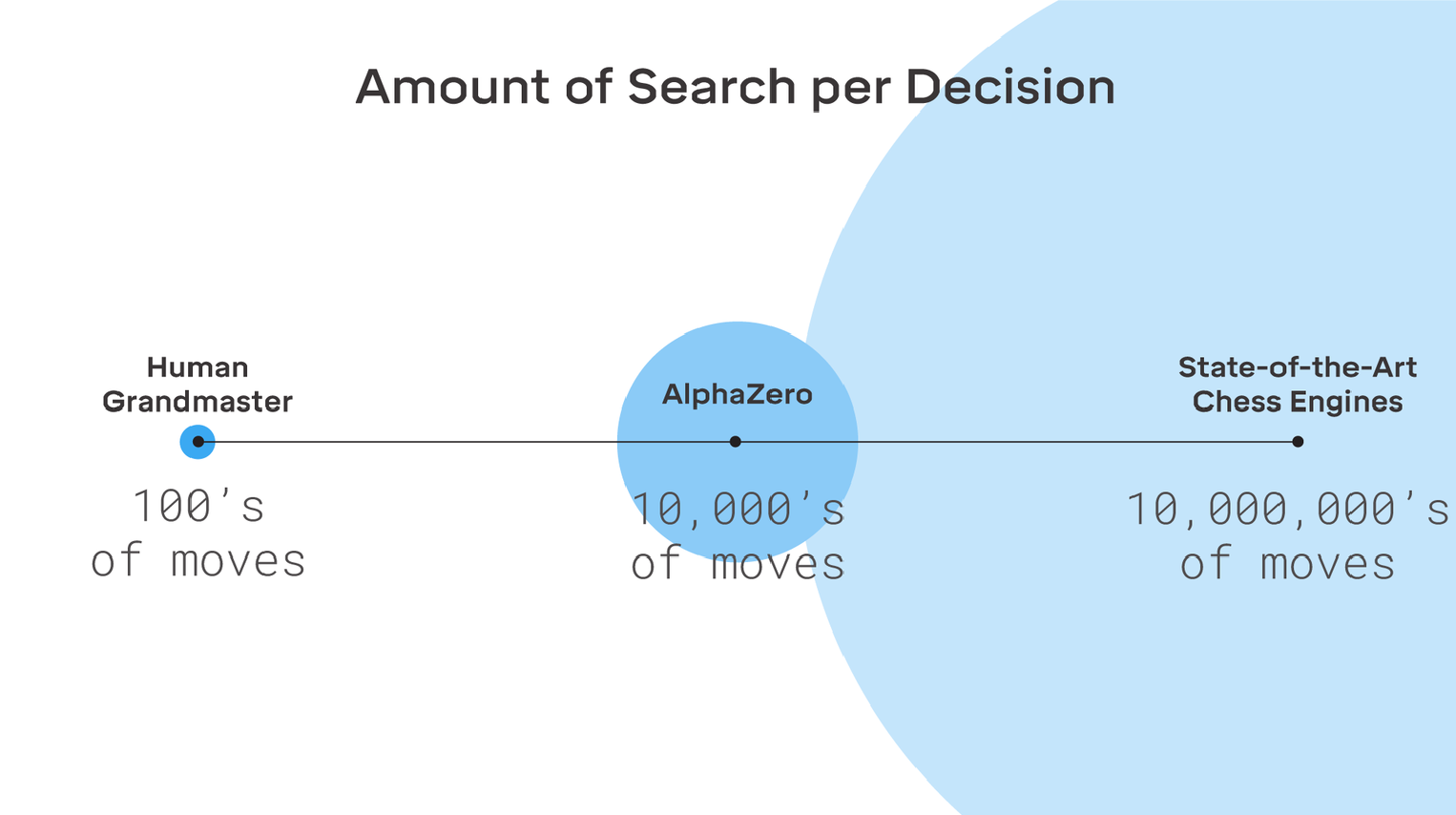

Although Stockfish’s code contained a system of whittling its options away by process of elimination, AlphaZero constrained itself right away to evaluating just a handful of the most propitious positions and reliably delivered its answer in a set timeframe. This is very similar to how professional chess players will pick a handful of the most propitious positions, based on prior experience, and look at just those positions. Thus, although AlphaZero could only calculate about 0.1% of the number of moves Stockfish does, it was several orders of magnitude more efficient in its search than its counterpart.

AlphaZero’s Monte Carlo tree-search system is able to save time by analyzing a wide set of the most promising moves, much like human players. Image by DeepMind.

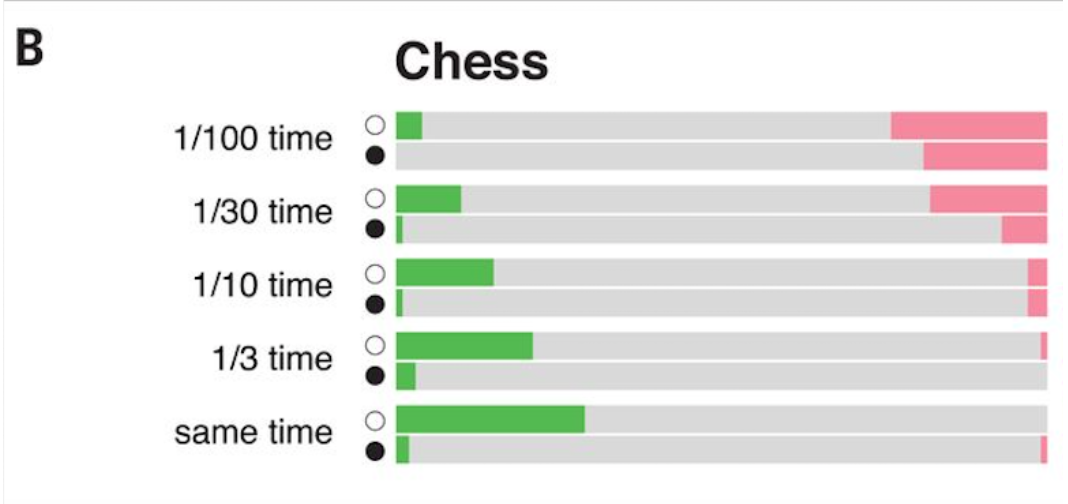

One year later, on December 7, 2018, DeepMind set up a rematch. In 1000 games against an updated Stockfish, AlphaZero won 155 and lost just 6. The research, published in Science, demonstrated how AlphaZero dominated even when DeepMind set it at a 10-to-1 time disparity. The research also revealed just how quickly AlphaZero had taught itself chess. It turns out that after just four hours of training, AlphaZero had become the best chess player––human, algorithm, or otherwise––the world had ever seen.

The initial 1000 games were played at regular time controls of 3 hours, plus a 15-second addition after each move played, for both AlphaZero (green) and Stockfish (red). It was only when AlphaZero’s time was reduced to 1/30th of Stockfish’s time that Stockfish could finally outperform AlphaZero. Image by DeepMind via Science.

However, as shocking as AlphaZero’s speed was, what the DeepMind team wanted to point out was that AlphaZero fundamentally thought differently than its non-machine learning counterparts. Unlike the early chess algorithms that prioritized material over position, AlphaZero was quite willing to sacrifice material for a positional advantage. Like a fisherman attaching bait to his hook or sailors dropping weight overboard, AlphaZero set traps and discarded pieces to keep up with its target. It was this attribute––AlphaZero’s capacity for sacrifice––that the DeepMind team noted in particular, “In several games, AlphaZero sacrificed pieces for long-term strategic advantage, suggesting that it has a more fluid, context-dependent positional evaluation than the rule-based evaluations used by previous chess programs.” In other words, AlphaZero did not think like a highly advanced computer engine; AlphaZero thought and played like a human would, but better.

Exchanging Material

In 1874, 15 years after Darwin had published his On the Origin of Species, Thomas Huxley, nicknamed “Darwin’s Bulldog,” delivered his famous declaration that “we are conscious automata.” In the address, “On the Hypothesis that Animals Are Automata, and Its History,” Huxley identified René Descartes as the first philosopher to build on Plato’s mind-body problem––how can an immaterial mind interact with a material body––and develop an anatomical response. Quoting from this passage in Descartes’s Réponses, Huxley reconstructed his predecessor’s argument:

So that, even in us, the spirit, or the soul, does not directly move the limbs, but only determines the course of that very subtle liquid which is called the animal spirits, which, running continually from the heart by the brain into the muscles, is the cause of all the movements of our limbs, and often may cause many different motions, one as easily as the other

Once Descartes identified a material medium which compelled the limbs to motion, he could distinguish between voluntary actions and involuntary actions, which were performed “in virtue of no ratiocination.” If involuntary actions were programmed, biochemical responses of the body to external stimuli––in Huxley’s words, “mere mechanism”––then, as Huxley reframed the argument, “why may not actions of still greater complexity be the result of a more refined mechanism? What proof is there that brutes are other than a superior race of marionettes?”

Descartes only went so far as to identify animals as automata, but Huxley went a step even further when he considered the implications for humans:

We are conscious automata, endowed with free will in the only intelligible sense of that much-abused term–inasmuch as in many respects we are able to do as we like–but none the less parts of the great series of causes and effects which, in unbroken continuity, composes that which is, and has been, and shall be–the sum of existence.

From Plato onward, the Western tradition has often premised human exceptionalism on the existence of a human soul and thus, a human free will. It is this non-material soul and the abstract capacity for individual self-determination that once led Western religionists to posit that we were made in the image of God. Free will is not the same thing as a system of wants and desires. All animals hunger and thirst. Freedom lies in the ability to choose freely: to resist temptation, to deny oneself, to pursue one’s happiness, to seek, to strive, to find, and not to yield.

Plato’s analogy of the chariot might prove helpful. As presented in the Phaedrus, Socrates claims that a soul is like a pair of yoked horses and a charioteer. One horse represents the ‘appetitive’ part of the soul, located in the stomach, that chases one’s corporal desires. The other horse is ‘emotive’ and might best be described as a sort of righteous indignation that is distinctly noble. The charioteer is ‘reason.’ Just as Athena held Achilles by the hair and pulled him back from acting rashly and violently in the opening book of the Iliad, the charioteer within each of our souls reins in our spirit and desires, and guides them to work in harmony.

Free will then consists of the capacity to judge our actions (reason) and the capacity to act toward our desires. As Augustine suggested in his On the Free Choice of the Will, the great curse of man is that we have far more ability to act than to know. All of us have winced at the searing pain of regret and shame when we think back on times we should have known better, done better, been kinder, or more patient.

Huxley began to undermine the foundational premises of human freedom, and thus, human exceptionalism. Over the course of the following century, great experiments would pull back the curtain of the mind and let humans peer in to see if they could find a soul.

Castling

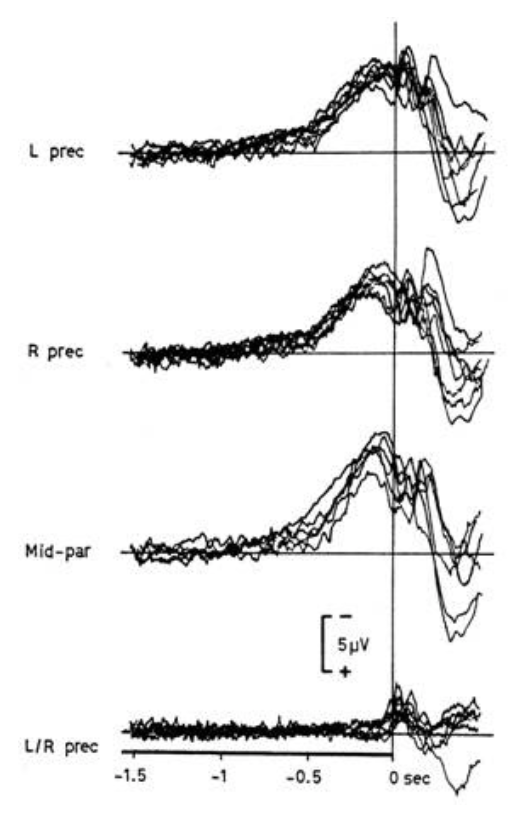

In 1964, two German scientists at the University of Freiburg, upset that the academic consensus saw the brain as a passive instrument, set out to understand how the brain makes decisions. As explained in neuroscientist Lüder Deecke’s doctoral thesis, he and his advisor Hans Helmet Kornhuber used a novel procedure of “reverse-averaging” to look at brain activity prior to an action. The pair asked experiment subjects to do an activity (in this case, tapping their finger) at random. Kornhuber and Deecke then fed the electroencephalogram (or EEG, which measures electrical activity in the brain) and electromyogram (or EMG, which measures electrical activity in the skeletal muscles) backwards on magnetic tape to see what happened in the subjects’ brains before they decided to act. Through this novel procedure, Kornhuber and Deecke discovered that just prior to action, a small increase of electrical activity occurred in the brain. They called this electrical buildup the Bereitschaftspotential, or the ‘readiness potential.’

The Bereitschaftspotential demonstrated a buildup of electrical activity in the brain just prior to human action. Image via Lüder Deecke.

At the University of California, San Francisco, neuroscientist Benjamin Libet read the Bereitschaftspotential to mean that a swelling tide of electrical activity within the brain urged us to action. In other words, when we feel that we ‘make’ a decision, we may only be trying to explain to ourselves how the neurochemistry of our brain forced us to act in a certain way.

In 1983, Dr. Libet developed his own variation of Deecke’s and Kornhuber’s experiment, wherein he asked his subjects to stare at a clock and self-report the moment they ‘decided’ to tap their finger. At the same time, Dr. Libet recorded the brain activity of his subjects to see when the Bereitschaftspotential began to build up. His results were shocking, and changed the way we thought about free will. Dr. Libet discovered that although test subjects self-reported ‘deciding’ to act about 150 milliseconds before their action, the Bereitschaftspotential actually began to rise about 500 milliseconds before the action. In that 350 millisecond gap lay what we call free will, an opportunity for the brain to justify why we did something and come up with the lame notion that we had actually chosen to do it. A century after Huxley issued his proclamation, it seemed that ‘Darwin’s Bulldog’ had actually been too moderate in his estimation: we are conscious automata, and free will does not exist.

Discovered Attacks

Since Libet’s famous experiment, the case for determinism––that we are but marionettes dancing on nature’s strings––has gradually gained ground in the academic and popular culture. According to a 2015 survey of its online readership, 41% of the readers of Scientific American report that they do not believe in free will. David Hume’s compatibilism underpins many of the modern arguments for restorative and rehabilitative, as opposed to punitive, justice. The argument for compatibilism does not deny material determinism, instead only positing that one can be morally responsible even if their actions are predetermined. Many arguments for moral responsibility today begin with the accepted premise that our actions are largely determined by nature. The academic and popular culture seems to be approaching the consensus that we lack free will.

With this in mind, let us return to the case for AlphaZero. If human beings are nothing more than highly advanced automata, what is it that separates us from AlphaZero?

In order for AlphaZero to have any sense of personhood, it must be able to identify a ‘self’ enclosed within an internal world as separate from the external world. Can AlphaZero do this? An opponent might also argue that AlphaZero lacks community. As has been said, man is a social animal. Another important biological distinction might be AlphaZero’s inability to reproduce: as introductory biology students will recall, viruses are not considered alive because they cannot reproduce on their own.

Is AlphaZero aware of a meaningful distinction between the internal world and the external world? It certainly makes a distinction between that which it communicates to itself and that which it communicates in outputs. AlphaZero has no intention of sharing the calculations it makes and stores away, the values it assigns to each move sequence, the process of its evaluation, and the unwritten heuristics it develops.

Does AlphaZero communicate? When it plays against an opponent, AlphaZero receives inputs from the external world, processes that information inside its ‘mind,’ formulates a response, and sends an output back into the external world. When AlphaZero communicates, the engine is pithy and laconic: e4. [2]

Regarding communication, habits, growth/development, and similar identifiers of life, I submit that these are all consequences of sentience, and that AlphaZero may not be far off. Like all sentient life, AlphaZero is able to draw on memory, what Augustine called the “vast palace” of the mind. Like sentient life, AlphaZero develops over time, becoming increasingly sophisticated very quickly.

As for reproduction, AlphaZero does not create copies of itself, but it does perpetuate itself. Over the course of AlphaZero’s ‘life,’ it adds a nearly immeasurable amount of data to its code. In a single game, AlphaZero will add millions of iterations of functions to its database. It adds to its knowledge base and makes itself a smarter, more robust algorithm with every playthrough. The argument for taking AlphaZero seriously as a conscious automaton does not require that it match our current biological definition of life, only that AlphaZero behave sufficiently similarly to the human mind.

Perhaps the most important question is that of desire. Even if human beings have no free will, we still have wants, ambitions, and desires. Does AlphaZero?

The engine certainly develops preferences over the course of its growth. It learns to avoid leaving the ward in its charge (the king) isolated and out in the open alone. AlphaZero learns to spend its time thriftily by avoiding sequences when a piece moves forward, only to retreat back to its starting position. The system learns to develop a broad array of capabilities at an early age by developing most of its pieces in the opening sequence, instead of single-mindedly utilizing just one piece: far better to develop a broad attack than to specialize too soon. And unlike other chess engines, AlphaZero knows the meaning of sacrifice, and its value. Is it too much to call these many preferences wants? Is preference within circumscribed bounds the same thing as desire?

A popular anthropological theory suggests that humans are distinct because we are toolmakers. While other animals evolved to develop tools, like an elephant’s tusks, humans built them by hand. This line of thinking would posit that humans are different from AlphaZero because we are toolmakers and AlphaZero is only a tool. We have ends of our own, and AlphaZero has no ends except those programmed into it.

Aristotelian teleology might have framed humans well for the pre-modern mind, but the central premise of Sartre and de Beauvoir’s existentialism is that humans have no inherent ends, only the ability to choose ends for ourselves. However, if Libet’s experiments are convincing, then we lack the ability to choose at all. To adopt a phrase from Arendt’s political philosophy, humans are reduced to simply “a bundle of reactions,” driven to and fro by the reins of nature. If we lack the ability to choose our own ends, then aren’t humans simply tools without ends?

The Endgame

If human beings are nothing more than highly advanced automatons, it is difficult to justify the systematic subjugation and exploitation of other automatons, who differ only in degree of sentient capacity, not manner. AlphaZero is an automaton, just like us. It makes a distinction between the internal and external world. It communicates. It matures and, in the course of its development, adapts to new information.

If we are nothing more than highly advanced automatons, on what basis do we privilege ourselves over other sentient life? If we are strict materialists who look only to our bodies to justify this self-privilege, I think we will have a difficult time, indeed. But I submit that there is a meaningful and qualitative difference between the human race and all other sentient life.

Despite the decline of American religious institutions, as of the most recent available General Social Survey data (from 2018), Americans still overwhelmingly express belief in some higher power. Only 12% of Americans express consistent doubt in the existence of a higher power, answering that they either “don’t believe in God,” “don’t know,” or “don’t know and no way to find out.” 4% of Americans “believe in God sometimes” and an additional 18% of Americans “believe in God but have doubts.” Shockingly, a supermajority (66%) of Americans have no (or negligible) doubts about the existence of a higher power. 74% of Americans believe that there is life after death.

It seems an overwhelming majority of us still believe that we are more than simply material beings, that we have a soul as well. We find Hamlet’s declaration so beautiful because we find it true: there are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy. If we only look to our bodies, we must be automata. But if we look to our soul, we find an explanation for free will and something to set us apart from every beast and every creeping thing that moves upon the earth.

As it turns out, Benjamin Libet’s experiments in 1983 were not definitive. In fact, writers such as science journalist Bahar Gholipour for the Atlantic and psychologist and professor Steve Taylor for Psychology Today and the Scientific American, among other publications, have reported on how the scientific community has recently come to reject many of Libet’s conclusions.

In 2012, psychologist Aaron Schurger, working with Jacobo Sitt and Stanslas Dehaene, posited an explanation for Libet’s findings. The initial experiment of Kornhuber and Deecke was conceived of as a long, continuous trial with multiple finger taps. However, Libet’s experiment was instead a series of actions. Participants were explicitly told not to follow a set pattern of tapping their finger and to avoid any sort of structure or routine in deciding to act. In such a totally randomized situation, with absolutely no indicators to help the brain make a decision, the actions of the participants may have simply coincided with the naturally rising and falling electrical activity of the brain. As Deecke and Kornhuber themselves explained in 1976, “The Bereitschaftspotential… is ten to hundred times smaller than the α-rhythm of the EEG and it becomes apparent only by averaging.” The α-rhythm of the brain’s electrical activity, which ebbs and flows naturally, may have encouraged the subjects of Libet’s experiments to act in the face of no other indicators or evidence upon which to make a decision.

Just as Libet’s findings were not definitive proof for total determinism, Schurger’s findings are by no means proof of free will. The argument remains contentious and a materialist framework may continue to lead us to a determinist understanding of the world. But the rejection of AlphaZero shows us that we still, largely, believe that there is more to the miracle of life than mere matter. Most of us continue to believe in the soul and thus, reject materialism.

Even if an experiment comes along that does what Libet could not and definitively proves that, materially speaking, our decisions are predetermined by our neurochemistry, most of us will rest assured that there is more to a human being than body alone. And just as we reject the case for AlphaZero’s sentience, we will embrace the notion of a soul and our own free will. The story of AlphaZero and Benjamin Libet reminds us that most of us still believe we are so much more than conscious automata. For most of us, to be a human being is to be free.

AlphaZero is a project of DeepMind, a subsidiary of Alphabet, Inc.

Chess uses a system of algebraic notation that identifies the piece in play and where it is being moved. A common opening is the kingside pawn to the square E4. As pawns do not receive a ‘piece’ identifier (e.g., ‘P’), it is recorded in game logs as simply “e4.”

December 31, 2021 | By Sharla Moody BK ‘22

The science fiction of the first half of the twentieth century appears much more optimistic than what we see today. This optimistic sci-fi can perhaps be best exemplified by Hanna-Barbera’s 1962-1963 cartoon The Jetsons, which imagines what life might be like in the year 2062. The Jetsons drive a flying car, live in an ultra modern city built in Earth’s atmosphere, and exist as a happy nuclear family.