Life City

February 1, 2023 | Amelia Dilworth BR ‘23

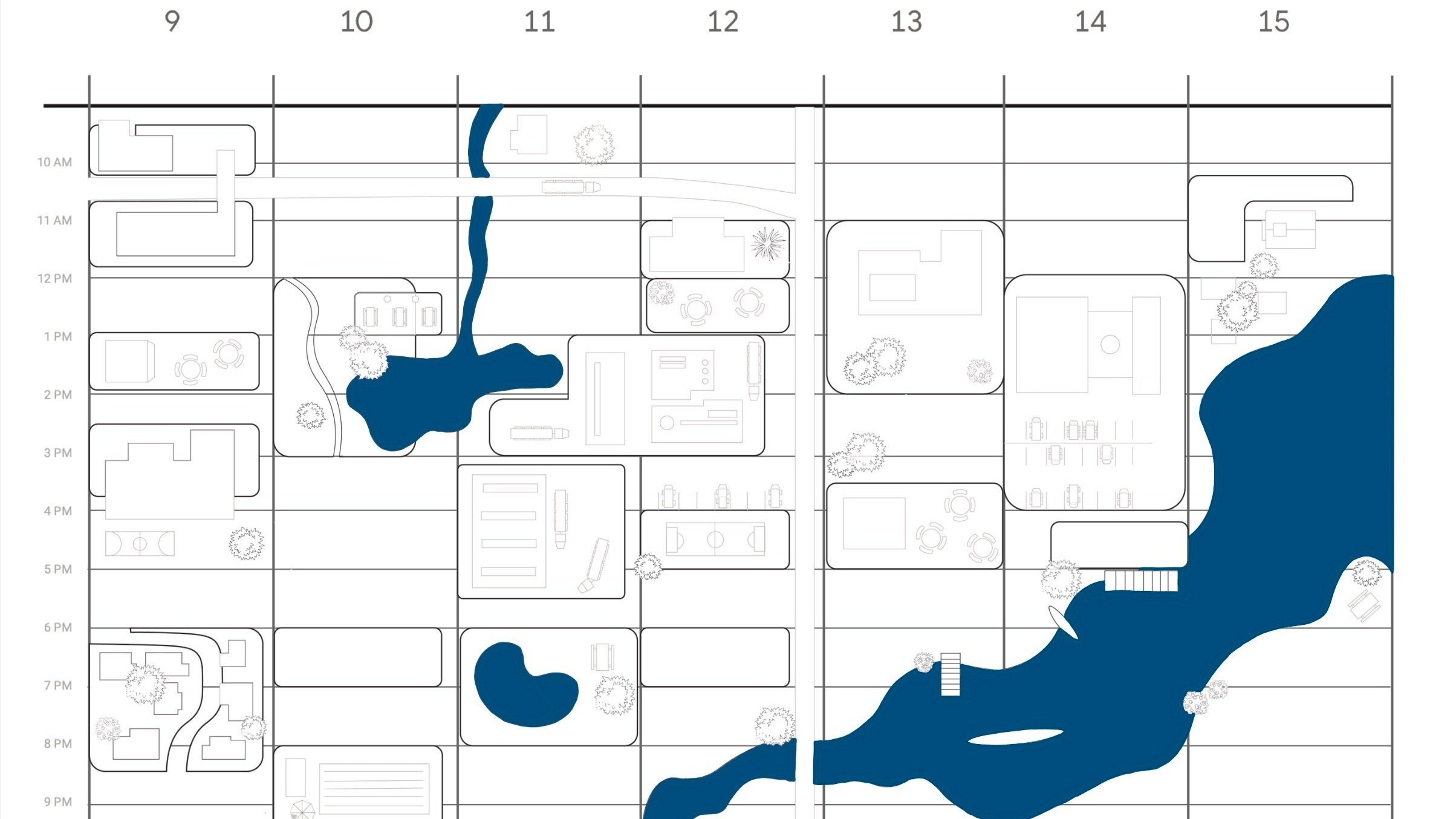

image description: city sketch on Google calendar

Sometimes when I look at my Google Calendar, I think of each hour as a city block, and all my events as buildings I’ve constructed in the city of my life.

And sometimes, I think—this is not a city I’d want to live in.

I wouldn’t want to live in a city with buildings so close to each other, with no green space for play or recreation. I wouldn’t want to live in a city with so many schools and offices but only a few ice cream shops and swimming pools. I do try to build a beautiful, desirable city for myself—but I find the city easily becomes overrun with unusable surface parking lots in between classes, and overscheduled with buildings constructed one on top of the other.

I think about Central Park—in a place as densely built up as New York City, the city would be unlivable without a place for freedom. Giving up land in the heart of New York City for green space may feel like a ridiculous, radical, irrational sacrifice. How many billions of dollars could that land be worth if it was used for real estate?

But without Central Park, the whole city would be worthless. If that same amount of green space were chopped up and divided into little medians throughout the city, that would be an easier sacrifice—but it wouldn’t have the same impact. New York would be a different city without that space for rest and recreation.

And it’s hard to take time off—to build parks like this across our own lives. But science is clear that we think better when we give ourselves time to rest rather than constantly engaging in long-term, high-intensity mental stimulation. Neuroscientists have found that “when we are resting the brain is anything but idle and that, far from being purposeless or unproductive, downtime is in fact essential to mental processes that affirm our identities, develop our understanding of human behavior and instill an internal code of ethics.” [1] We actually need rest to learn, be creative, and process the information we receive from work.

In 2021, The Wall Street Journal reported that half of the people using Microsoft Teams “respond to chats in five minutes or less,” and there was a 10% increase in emails answered after working hours. [2] During the pandemic, remote work sprawled across the boundaries between home and office, now capable of colonizing every moment of employees’ time—resulting in unprecedented stress, burnout, and resignations. [3]

The white-collar American workforce, which most college students intend to join, is working more than ever before. And they’re also more stressed than ever, leading to “lack of interest, motivation and energy at work,” “cognitive weariness,” and eventually “[raising] the risk of degenerative brain diseases such as dementia and Alzheimer’s.” [4] Overwork and chronic work stress makes us worse employees, at a cost to our own minds.

Maybe hyperproductivity is, actually, a waste of time.

In Leviticus 23:22, a passage from the Old Testament, God tells the Israelites, “And when you reap the harvest of your land, you shall not reap your field right up to its edge, nor shall you gather the gleanings after your harvest. You shall leave them for the poor and for the sojourner: I am the Lord your God” (ESV).

God gives the Israelites a zoning code that prevents them from sucking all the possible worth out of their land. And if we view our time as land, this means that God calls His people to let others benefit from their blessings, instead of working to the point of exhaustion.

God isn’t saying, “you shall not sow your field right up to its edge, so you can build a golf course.” We aren’t leaving unharvested time in our lives for self-serving leisure—we’re leaving time to do good. Harvesting time but sharing it with the “poor and the sojourner” might look like leaving time to volunteer, time to vote, time to bring food to a sick neighbor.

Our society often sees time as a dichotomy: work, or pleasure. But the approach to urban planning/time management/agriculture/social justice outlined in Leviticus suggests that life should include some time to be productive, without being profitable. The cities of our lives were never meant to be factories and warehouses from dawn to dusk with extractive pleasures lurking on the weekends.

This is where the Central Park metaphor falters: New York City reaps its fields all the way to the edges, building on every inch of the island. Central Park isn’t wild and unscripted and sublime—–it has carefully measured boundaries. It has hotdog stands. Central Park is the bare minimum required to keep functioning at an unsustainable, break-neck speed.

Central Park only made the surrounding real estate more valuable, squeezing even more worth out of the land. And, when it was built in 1858, Central Park displaced a thriving Black neighborhood. Beneath the illusion of freedom and rest, Central Park is an exploitative real estate maneuver built on stolen land.

If we see our calendars as land, Christians would argue that God is calling humans to a type of rest even more precious, more costly, than property in Manhattan. A time of genuine freedom.

In Deuteronomy, God commands his people, “Observe the Sabbath day, to keep it holy. As the Lord your God commanded you. Six days you shall labor and do all your work, but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the Lord your God. On it you shall do no work…. You shall remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and the Lord your God brought you out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm” (Deuteronomy 5:12-15, ESV).

And I think that college students like myself, with our overfilled Gcals and five-year career plans, understand better than anyone else in a modern, technological society that “not reap[ing] your field right up to its edge” comes from the same ethos as keeping a Sabbath, because time is our land. It’s our investment in our future, so we aspire to be as productive and fruitful as possible. We reap and sow extracurriculars and classes on every acre of our schedule. Productivity is not inherently bad—but we’re afraid of giving up time in our schedules to worship an unseen God the same way that ancient people must have been afraid of sacrificing the best of their harvest and sharing the remainder with the poor.

But I’ve found that being willing to sacrifice time and space requires believing in a God who is worth your time. In Deuteronomy, God tells the Israelites to remember that He brought them out of slavery to remind them why He deserves their time: He is the God who redeems, who provides, who brings his people life and freedom. He is a God who is worth more than anything I could do for myself. Christians today aren’t called to follow Old Testament commandments, but if we serve the same God, living for Him still requires prioritizing Him above all else. Christians believe that we don’t just owe Jesus a seventh of our week, we owe Him our entire lives.

So I don’t want a God I can fit into my schedule like getting a flu shot or changing the Brita filter. A convenient God wouldn’t be worth serving. My God is more than a church service in my Gcal— He is the master of Time itself. He isn’t a single building in the city of my schedule, He’s the one who created the earth and the oceans that roar over it. Time was never mine to begin with. My life and my land belong to Him.

This is the only way I can find real, genuine rest—to fully surrender control to God, to rejoice in the fact that He always has and always will provide for me.

So I’ve found that taking time to go to church when I have homework due on Monday, or pausing to read my Bible even on a hectic morning, are the choices that actually bring me peace. I do enjoy being busy—but I don’t need an over-structured calendar to feel fulfilled. I can’t harvest time with God—but I can’t harvest swimming in the ocean or watching the sunrise from the mountaintop, either. I refuse to build office parks in the most beautiful parts of my city. I’ll reconstruct the city of my life around Him.

I write all of this, but I must confess— again and again I find myself building my city into the edges of a rising ocean, raising skyscrapers into sandy desert winds, wondering how long I can get away with an unsustainable, deceptively “productive” life.

But when hurricanes come and earthquakes rumble and the teetering metropolis of my overscheduled life begins to crumble, I’m forced to remember that I’m not in control—He is. When the water sweeps away my streets I remember that we aren’t all-powerful.

And it’s comforting to remember that I’m not the architect of my own destiny. I don’t have to have the shaky city of my whole life planned out.

When I’m awash in unexpected delays and my schedule falls apart, I remember that God is the one who has dominion over time and space, not me. He calms the sea because he spoke it into existence. When my days feel fuller than ever, that’s when I need God most.

So, God, teach me to let my land rest and to let my soul be still. Teach me that time and space belong to you. And when I forget these things, when I’ve built my own cities and say I did this for myself—let the hurricanes thunder onto my shores, bring me to my knees, remind me that I am made to serve the God who saves.

[1] Ferris Jabr, “Why Your Brain Needs More Downtime.” October 15, 2013. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/mental-downtime/

[2] [3] Te-Ping Chen and Ray A. Smith, “American Workers Are Burned Out, and Bosses Are Struggling to Respond.” December 21, 2021. https://www.wsj.com/articles/worker-burnout-resignations-pandemic-stress--11640099198

[4] Bryan Robinson, “How Chronic Work Stress Damages Your Brain And 10 Things You Can Do.” May 2, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/bryanrobinson/2022/05/02/how-chronic-work-stress-damages-your-brain-and-10-things-you-can-do/?sh=1bfcf4165795

February 1, 2023 | Lily Lawler BK ‘23

Each sunset with clouds draped around it and every birdsong I heard in the morning pointed my face towards God’s undeniable glory. The infinitely unfolding beauty in this world was enough evidence for me that God is present with us.